What You’ll Find Here

- The Engine Room: What Makes Mountain Weather So Wild?

- Decoding the Forecast: Your Pre-Trip Lifeline

- The Safety Playbook: Strategies for Every Condition

- Gear Up: The Non-Negotiable Kit for Variable Mountain Weather

- Your Mountain Weather Questions, Answered

- A Deep Dive: The Infamous Mountain Lee Wave (and Rotor Clouds)

- Putting It All Together: Your Pre-Hike Weather Checklist

Let's be honest, checking the weather for a hike shouldn't be this stressful. You look at the forecast for the nearest town—sunny, 75 degrees, perfect. But then you get up on the ridge, and suddenly you're in a freezing, howling wind with clouds rolling in out of nowhere. Sound familiar? That's mountain weather for you. It plays by its own set of rules, completely different from the valleys below.

I've been caught out more times than I care to admit. Once, on what was supposed to be a simple day hike, a sunny morning turned into a full-blown sleet storm above the tree line. My light jacket was useless, my hands went numb, and the trail disappeared under a white blanket. It was a harsh, stupid lesson. Since then, I've made it a point to understand this beast. This guide isn't about scaring you off the trails. It's the opposite. It's about giving you the knowledge to read the signs, respect the conditions, and make smart decisions so you can enjoy the mountains safely, no matter what the sky throws at you.

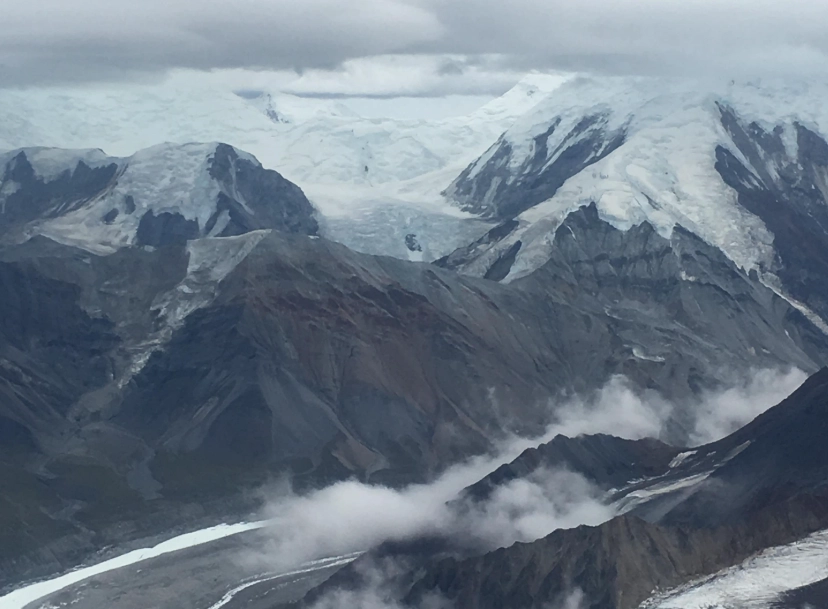

The Engine Room: What Makes Mountain Weather So Wild?

To predict it, you need to understand what's driving it. Think of a mountain as a giant obstacle in the sky's path. It forces everything—air, moisture, storms—to behave in extreme ways. It's basic physics, but the results are anything but basic.

Altitude is Everything (The Big Chill)

This is the big one. For every 1,000 feet (about 300 meters) you climb, the air temperature drops by roughly 3 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit (that's about 5 to 9 degrees Celsius). It's called the lapse rate. So, if it's a pleasant 70°F (21°C) in the trailhead parking lot at 5,000 feet, it could be a chilly 50°F (10°C) at a 10,000-foot summit. That's a massive difference you feel in your bones.

And it's not just the cold. The air gets thinner. Less air pressure means your body works harder, you dehydrate faster, and the sun's UV rays are more intense. You can get sunburned and hypothermic on the same day. Fun, right?

Mountains Shape the Weather (The Great Divider)

Mountains act like a colossal wall. When moist air from an ocean or lake hits a mountain range, it has nowhere to go but up. As it rises, it cools, condenses, and forms clouds and precipitation. This is the windward side, and it's often wet and stormy.

By the time the air crosses the crest and spills down the other side—the leeward side—it has lost most of its moisture. This creates a rain shadow, a much drier area. The landscape can change completely from one side of a pass to the other. I've hiked from dripping, foggy forests into dry, sunny alpine meadows in under an hour because of this effect.

Seasonal Shifts Aren't Gentle Here

Mountain seasons are more like distinct, volatile personalities than gradual changes.

- Spring & Fall: These are the truly unpredictable seasons. You can get all four seasons in a single day. Warm sun, followed by a snow squall, then rain, then sun again. These are my favorite times to go out, but they demand the most flexibility and gear.

- Summer: Ah, hiking season. Afternoon thunderstorms are the headline act. They build with terrifying speed. Blue skies at 10 a.m. can turn into lightning, hail, and torrential rain by 2 p.m. The rule is simple: be off the peaks and ridges by early afternoon.

- Winter: It's a different world. Stability is the name of the game, but the cold is severe and relentless. The main dangers are extreme wind chill, whiteout conditions during storms, and avalanches. Understanding avalanche forecasts from centers like the American Avalanche Association is non-negotiable.

So, how do you make sense of all these chaotic factors when planning your trip? You learn to read the forecast like a pro.

Decoding the Forecast: Your Pre-Trip Lifeline

Looking at an app icon showing a sun or a cloud isn't forecasting; it's guessing. You need details, and you need them for the right place.

Where to Get Reliable Mountain Weather Intel

Forget the generic weather app on your phone for anything beyond the valley floor. You need specialized sources.

| Source | What It's Good For | My Personal Take |

|---|---|---|

| National Weather Service (NWS) weather.gov | Official, detailed forecasts for specific mountain zones, including discussions written by meteorologists explaining their reasoning. The point forecasts for exact coordinates are gold. | This is my #1, always. The "Forecast Discussion" tab is where the real nerdy insights live. It's not always user-friendly, but it's the most authoritative. |

| Mountain-Focused Websites & Apps (e.g., Mountain-Forecast.com) | Forecasts for specific peaks and elevations. They graphically show conditions from base to summit. | Incredibly useful for visualizing the altitude factor. But treat them as a guide, not gospel. Cross-reference with NWS. |

| Park & Forest Service Websites (e.g., nps.gov for US National Parks) | Local conditions, trail-specific alerts, webcam feeds, and ranger observations. They know their terrain intimately. | An underutilized gem. A ranger's note about "lingering snow on north-facing slopes" is more valuable than any general forecast. |

| Local Outdoor Shops & Guiding Services | Word-of-mouth, on-the-ground intel. They live and breathe the local mountain weather patterns daily. | Stop in and buy a map or some gear, then ask. They'll often give you the straight story you won't find online. |

Key Terms You Need to Understand

Forecasts are full of jargon. Here’s what matters:

- Chance of Precipitation (PoP): 30% doesn't mean 30% of the area will get rain. It means there's a 30% chance it will rain at any given point in the forecast area. In mountains, that chance is often concentrated on windward slopes.

- Wind Speed & Gusts: A forecast for "winds 15-25 mph, gusts to 40" is standard for a ridge. 40 mph is enough to make walking difficult and dangerous near edges. It also creates brutal wind chill.

- Freezing Level: The altitude where the temperature hits 32°F (0°C). Crucial for knowing if precipitation will be rain or snow. In spring/fall, this level can move up and down the mountain through the day.

Okay, you've studied the forecast. Now, what do you actually do with this information? It all comes down to smart planning and knowing when to turn around.

The Safety Playbook: Strategies for Every Condition

Knowledge is pointless without action. Here’s how to translate your weather intel into safe decisions on the ground.

The Summer Game: Dodging the Afternoon Thunderstorm

This is the most common and dangerous mountain weather hazard for hikers.

- Start Early, Seriously Early: Aim to be at the trailhead at sunrise. Your goal is to be heading down from high, exposed areas by noon or 1 p.m. at the latest.

- Watch the Sky (Not Just Your Phone): Learn the signs. Puffy cumulus clouds building vertically into cauliflower shapes (cumulus congestus) are the warning. When they turn dark at the base and start to flatten into an anvil shape (cumulonimbus), the storm is imminent. If you hear thunder, you are already in danger of a lightning strike.

- Know Your Escape Route: Before you go up, identify where you can descend quickly to lower, forested ground. Don't wait until the storm hits to figure this out.

The Winter & Shoulder Season Game: Managing Cold and Storm

Here, the enemy is exposure and losing your way.

- The Layering System is Law: Base layer (wicking), insulating layer (fleece/puffy), and a waterproof/windproof shell. Never wear cotton—it's a death fabric when wet.

- Wind Chill is a Killer: Check the NWS Wind Chill Chart. A calm 20°F day is manageable. Add a 30 mph wind, and it feels like -4°F, with frostbite risk on exposed skin in as little as 30 minutes.

- Navigation Gets Hard: A sudden snow squall can reduce visibility to feet, not miles. Always carry a physical map, compass, and know how to use them. A GPS is a backup, not a primary.

But what about the gear? You can't just will yourself to be warm.

Gear Up: The Non-Negotiable Kit for Variable Mountain Weather

Your gear is your backup plan when the forecast fails. And it will fail sometimes. This isn't about buying the most expensive stuff; it's about having the right stuff, always in your pack.

The Core Four for Weather Survival:

- Insulation (The Puffy): A lightweight, packable down or synthetic jacket. It lives in your pack 365 days a year. When you stop for lunch on a windy summit, even in summer, you'll put it on.

- Rain Shell (Not a "Water-Resistant" Jacket): A true waterproof and breathable jacket with a hood. This is your main defense against wind, rain, and sleet. Pit zips for ventilation are worth every penny.

- Head, Hands, Feet: A warm hat (beanie), gloves (even light running gloves in summer), and an extra pair of wool socks. You lose a huge amount of heat through your extremities.

- Emergency Shelter: A lightweight emergency bivy sack or space blanket. If someone gets hurt and you have to stop moving, this can prevent hypothermia while you wait for help.

Look, I've met people on trails in jeans and a cotton hoodie. They often say, "I'm just going a short way." But a sprained ankle can turn that short way into a long, cold, dangerous wait. Carrying this kit is a habit, not a burden.

Your Mountain Weather Questions, Answered

Over the years, I've been asked the same things on trailheads and in forums. Here are the real answers.

Speaking of planning, let's talk about a specific, often misunderstood phenomenon that defines mountain weather in many regions.

A Deep Dive: The Infamous Mountain Lee Wave (and Rotor Clouds)

This is advanced-level stuff, but understanding it explains some of the most violent and strange winds you'll ever encounter.

When strong, stable wind flows over a mountain range, it can create a massive standing wave downwind of the peaks, like the wave that forms behind a rock in a stream. This is a mountain lee wave. Pilents know about these, but hikers and climbers feel their effects at the surface.

- The Sign: Lenticular clouds. Those smooth, lens-shaped, UFO-like clouds hovering over or downwind of a peak. They look stationary because the wind is constantly condensing air on the windward side and evaporating it on the leeward side. They are a mountain weather red flag for high winds aloft.

- The Danger at Ground Level: Beneath these smooth waves, the wind at the surface can be chaotic and terrifying, blowing up the slope or swirling in violent circles called rotors. I've been on a ridge where the wind was literally switching direction 180 degrees every few seconds, knocking me off balance. It's incredibly dangerous near cliffs.

If you see lenticular clouds, especially stacked like pancakes, expect extreme and unpredictable winds at high elevations. It's a day for a sheltered valley hike, not a ridge traverse. The NWS Mountain Weather Training Page has great technical details on this if you're curious.

Putting It All Together: Your Pre-Hike Weather Checklist

Let's make this practical. Run through this list before you ever put your boots on.

- Forecast Source: Did I check the NWS point forecast for my exact route elevation and the local land manager's site?

- Key Metrics: Do I know the expected high/low, wind speed/gusts, precipitation chance/type, and freezing level?

- Timing: Have I planned my day to avoid peak thunderstorm hours (noon-4 p.m.) or worst wind/cold?

- Gear Check: Are my core four (insulation, shell, hat/gloves, emergency shelter) in my pack, along with extra food and water?

- Plan B: Do I have a solid, less-exposed alternative route in mind if the weather deteriorates?

- Group Talk: Have I discussed the forecast and turnaround criteria with everyone going? (e.g., "If we see lightning or the winds exceed 40 mph sustained, we turn around immediately.")

Mastering mountain weather isn't about becoming a meteorologist. It's about developing a mindset of respect, preparation, and humility. It's about looking at a blue sky and knowing it's a temporary gift, not a guarantee. It's about feeling the first drop of rain or the shift in the wind and knowing what it likely means, and what your next move should be.

The payoff is immense. When you're prepared, you can experience the raw, beautiful power of a mountain storm from the safety of a treeline, or enjoy the crystal-clear, windless calm of a high alpine dawn that few ever see. You move from being a victim of the conditions to an engaged participant in the mountain environment. That's the real summit.

Stay curious, check the sky, and pack that puffy. I'll see you out there.

Comments