Quick Navigation

- So, How Do You Actually Find These Things? Your Route-Finding Toolkit

- Cracking the Code: What Do All Those Letters and Numbers Mean?

- Choosing Your Route: It's More Than Just the Grade

- Gearing Up: What You Actually Need on the Route

- The Unwritten Rules: Ethics and Leaving No Trace

- Answers to the Questions You're Probably Typing into Google

Let's be honest. When you're standing at the base of a crag for the first time, all pumped up and ready to go, the wall in front of you can look like... well, just a wall. A beautiful, imposing, slightly intimidating wall. Where are the holds? Which way do you go? Is that crack over there the line, or is it the face to the left? This moment of uncertainty, that gap between your stoke and the stone, is exactly what understanding climbing routes bridges.

I remember my first trip to Joshua Tree. Guidebook in hand, I was utterly lost. The book said "Start at the obvious left-facing corner." I saw three corners that looked equally obvious to my novice eyes. We wasted an hour fumbling around before a friendly local pointed out the actual start, a full body-length away from where we were trying to force our way up. That experience taught me more than any manual: knowing how to find, read, and choose a route isn't just helpful—it's fundamental to having a good, safe day out.

This guide isn't about fluff or theory. It's the stuff I wish someone had told me. We're going to break down exactly what a climbing route is (beyond just a line on rock), how the climbing community documents them, how to crack the code of those confusing rating systems, and how to pick the right line for your day. Whether you're scrolling through climbing routes on Mountain Project or squinting at a faded guidebook, you'll know what you're looking at.

So, How Do You Actually Find These Things? Your Route-Finding Toolkit

You can't climb it if you can't find it. In the old days, this meant word of mouth and painstakingly detailed descriptions. Now, we have more tools, but the core skills remain.

The Trusty Guidebook: Your Offline Bible

Despite all the apps, a good local guidebook is often unbeatable. Authors pour years of knowledge into them. They provide context, history, approach hikes, and often the most accurate topos (those diagrammatic drawings of the cliff). The detail can be incredible. A well-worn guidebook is a badge of honor. The downside? They get outdated, they're heavy, and if you're visiting a dozen areas, buying all those books adds up.

My tip? For your home crag or a major destination trip, buy the book. For scouting or a quick visit, supplements are available online.

Digital Beta: Apps and Online Databases

This is where most people start now, and for good reason. Mountain Project is the giant, crowd-sourced database. It's fantastic for breadth—you can find info on obscure crags in the middle of nowhere. The photos, user-submitted "beta" (tips on moves), and condition updates are gold. But remember, it's crowd-sourced. Ratings can be sandbagged or soft, descriptions can be vague, and sometimes the most popular climbing routes get all the attention while gems are overlooked.

Other apps like The Crag or 27 Crags are huge in Europe and offer similar, sometimes more polished, functionality. They're worth checking for your specific destination.

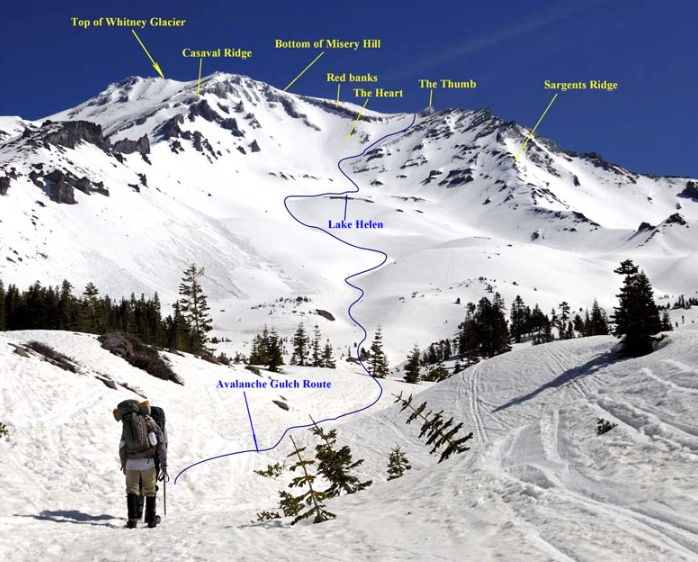

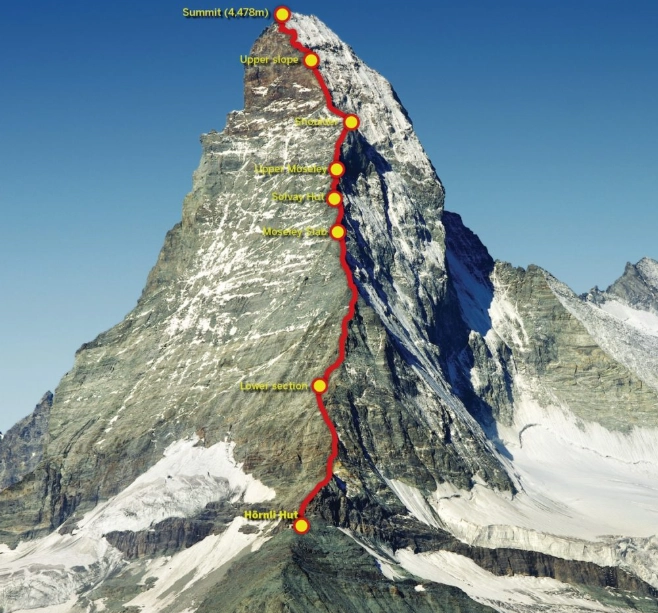

The Art of Reading the Rock: Your Most Important Skill

Tools are great, but your eyes and brain are the ultimate route-finding devices. This takes practice. You're looking for patterns.

- Discoloration and Wear: Popular routes often have darker, polished holds from countless hands and shoes. Look for lines of chalk (magnesium carbonate) marks. A faint vertical streak of chalk can be a dead giveaway for a common hand sequence.

- Logical Features: Does that crack system go all the way to the top? Does the face climbing lead to a obvious ledge? Routes tend to follow natural weaknesses in the rock—cracks, corners, dihedrals, and systems of edges.

- Fixed Gear: Spotting old pitons, bolts, or slings wrapped around horns can mark the path. But be careful—sometimes old, abandoned gear is from an entirely different, harder route or an old aid line.

Short paragraph? Sure.

Sometimes, the route finds you. You look up, and one line just calls out, looking more inviting and logical than the rest. Trust that instinct.

Cracking the Code: What Do All Those Letters and Numbers Mean?

This is where many new climbers get stuck. You see "5.10a", "5.11d", "V4", "E2 5c", "7a+" and your head spins. These are grading systems, and they're not universal. They're a shorthand for difficulty, but they're also a cultural artifact, full of quirks and historical baggage.

The most common system in the US for roped climbing is the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS). It starts at 5.0 (easy) and goes up... theoretically forever (currently up to around 5.15d). The "5" just means it's a technical rock climb (as opposed to a hike or a scramble). The number after the decimal indicates the difficulty. The letter (a, b, c, d) further refines it within that number. So 5.10a is easier than 5.10d.

But here's the kicker: it's not linear. The jump from 5.9 to 5.10 feels massive. The jump from 5.10 to 5.11 is another huge leap. And a 5.10 at one crag can feel like a 5.11 at another. Gritstone in the UK is famously sandbagged (deliberately undergraded). Some limestone sport crags are known for being "soft." You have to learn the local style.

For bouldering, it's usually the V-scale (V0-V17+), invented by John "Vermin" Sherman. Or the Fontainebleau scale in Europe (6A, 6B, 7A, etc.).

Let's put this in a table to see how some of the major systems loosely compare for roped climbs. Remember, this is a rough guide—direct translation is famously imperfect.

| YDS (USA) | French | British (Tech Grade / Adjectival) | UIAA (Continental Europe) | General Feel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.6 | 4 | 4a / Moderate | IV | Beginner terrain, big holds. |

| 5.8 | 5a | 4c / Difficult | V+ | Comfortable for most active people. |

| 5.10a | 6a | 5a / Hard Very Severe (HVS) | VI+ | The classic "intermediate" benchmark. Requires technique. |

| 5.11a | 6c | 5b / E1 | VII- | Solid intermediate/advanced. Powerful moves appear. |

| 5.12a | 7a+ | 5c / E3 | VIII- | Advanced. Often requires specific training. |

| 5.13a | 7c+ | 6a / E6 | IX- | Elite level. Dedicated training required. |

Why so many systems? History and rock type. The British system had to account for dangerous, poorly protected gritstone climbs, hence the two-part grade (technical difficulty and overall seriousness). The French system evolved on steep limestone where the physical difficulty was the primary factor.

The International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA) tries to promote standardization, but local traditions run deep. My advice? When you travel, climb a few well-known warm-ups to calibrate your personal "feel" for the local grades before jumping on your project.

Choosing Your Route: It's More Than Just the Grade

Okay, you've found a bunch of potential climbing routes. How do you pick? The biggest number you can maybe hang on to isn't always the right answer.

Ask yourself these questions:

- What's the style? Are you a crack climber? A face climber? Do you love overhanging jug hauls or delicate slabs? Picking a route that suits your strengths (or one that challenges a weakness you want to work on) is key.

- What's the protection like? Is it a well-bolted sport climb where a fall is generally safe? Or is it a traditional (trad) route where you place your own gear? If it's trad, what's the reputation? "Good gear" or "run-out" (big gaps between protection points)? Don't get on a run-out R-rated 5.10 if you've only climbed bolted lines. Resources like the Access Fund often discuss climbing ethics and local styles, which can hint at what to expect.

- What are the conditions? Is the route in the sun or shade? South-facing walls bake in summer. A north-facing dihedral might be an icebox in spring. Is the rock known to seep water after rain? Mountain Project comments and guidebooks are great for this.

- What's the descent? Seriously. This gets overlooked. Is there a walk-off trail? Do you need to rappel? Are the rappel anchors in good condition? A brilliant climb can be ruined by a nightmare descent in the dark.

Gearing Up: What You Actually Need on the Route

Your gear needs are dictated by the route type. Showing up to a trad crack with only quickdraws is a very short day. Here's a breakdown.

The Basic Rack (Tailored to the Route)

- For Sport Climbing Routes: Quickdraws (usually 12-16), a rope (70m is the modern standard), helmet, harness, shoes, chalk bag, belay device. Maybe a couple of spare slings for directional anchors on traverses.

- For Traditional (Trad) Routes: All the sport stuff, PLUS a rack of protective gear. This means cams (like Black Diamond Camalots, Wild Country Friends) in a range of sizes, nuts (stoppers), maybe hexes. The specific sizes depend entirely on the crack sizes on your chosen route—guidebooks often suggest a "standard rack." This is where research is non-negotiable.

- For Multi-Pitch Adventures: Everything above, plus more. Double the rack if it's a long trad route. Personal anchor systems (PAS), more slings, maybe a second rope for rappels, headlamps, extra layers, food, and water. A lightweight pack you can haul or wear. This is a bigger commitment.

I made the mistake once of borrowing a friend's rack for a crack climb. His cams were an older model that stuck in the parallel-sided granite cracks. I spent more time wrestling with stuck gear than actually climbing. Lesson learned: know your gear, and make sure it's appropriate for the rock type. Sandstone eats soft aluminum cams for breakfast.

The Unwritten Rules: Ethics and Leaving No Trace

Climbing outside is a privilege. Our behavior determines if access stays open. This goes beyond just picking up trash.

Chalk is a big one. Yes, it helps, but a giant, neon tick mark pointing to every single hold ruins the puzzle for the next person. Use it sparingly, and brush your ticks off when you're done. Some areas, like certain crack climbs in Indian Creek, have a "no chalk" ethic—locals use colored rock to see where to place gear.

Bolting is the hottest of hot-button issues. The general rule is: if a route can be safely climbed by placing traditional gear, it shouldn't be bolted. New sport climbing routes are often established by a small group of locals who have consensus about the line and its necessity. Don't ever add bolts to an existing route because you found it scary. That's a great way to get blacklisted in a community. If you're interested in the ethics, the National Park Service's climbing management pages often outline the specific rules for popular areas, reflecting the ongoing dialogue between climbers and land managers.

Respect wildlife. I've had to wait for a peregrine falcon to finish its meal on a ledge I needed to stand on. That's its home. I'm the visitor.

In the end, it's about respect. For the rock, for the people who came before you, and for those who will come after.

Answers to the Questions You're Probably Typing into Google

Look, at its core, this whole process—the finding, the decoding, the choosing, the climbing—is a conversation with the mountain. The guidebooks and apps are just someone else's notes from their side of the chat. Your job is to add your own voice to it. To feel the grain of the rock they described, to struggle on the move they warned was cryptic, to stand on the summit ledge they promised was worth it.

So get out there. Find a line that speaks to you. Do the homework, pack the right gear, and then... just start climbing. That's how routes stop being lines on a page and become stories you carry with you.

Comments